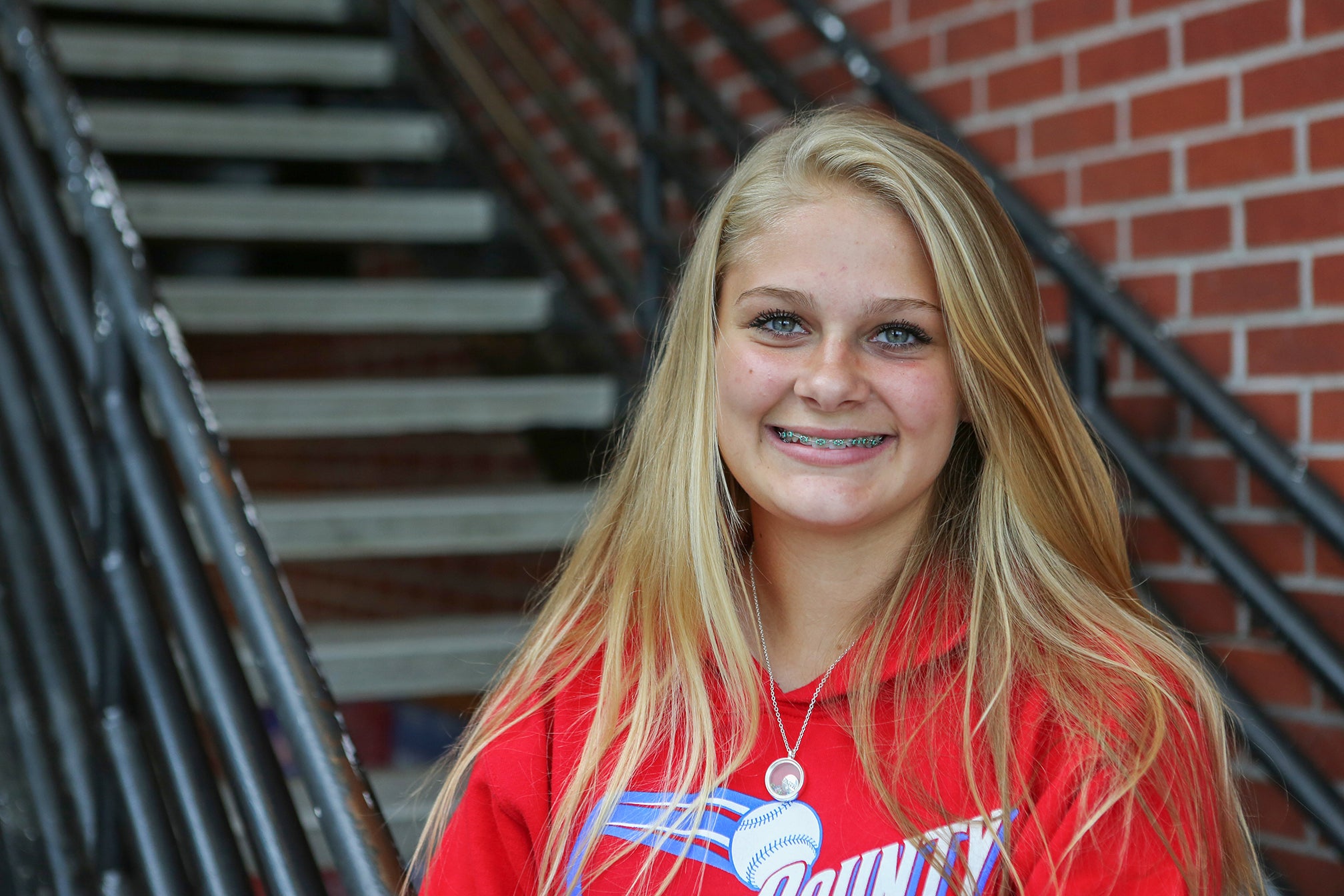

Deaf teen beats odds, excels in hearing-advantaged school

Published 12:16 pm Thursday, June 8, 2017

- Bella Herring, 14, poses for a photo at Lincoln County Middle School on May 22. Photo by Joshua Qualls

By Joshua Qualls

Bella Herring is not your average student, and that’s not because she’s deaf — although she goes to a hearing-advantaged school, she has found success in academics, student council and athletics.

The 14-year-old was born deaf and had gone to Kentucky School for the Deaf before she and her family moved to Stanford in 2014, but she never let her deafness hold her back when she started going to Lincoln County Middle School in seventh grade.

“Everything feels normal to me,” Herring said through interpreter Rita Zirnheld. “I communicate through sign language, and the most important thing is to make things easier for everyone else.”

Math teacher and volleyball coach Kellie Wilson said Herring’s positive attitude comes natural. Despite what makes her different from other students, she appears to have little to no trouble meeting expectations at the hearing-advantaged Lincoln County Middle School.

What’s more, her mom and her sister are also deaf, so she is surrounded by people who also experience deafness as a natural part of life. Her dad can hear, so he often acts as the communication liaison between them and the hearing-enabled, especially during her softball and volleyball games.

“Most of the time, I can get along by myself,” Herring said. “I’m pretty capable.”

Though capable she is, Herring’s teammates and Wilson have also taken it upon themselves to learn some signs and make communication a little easier.

“I knew she could do it! Because I myself a hairdresser working with hearing world everyday,” Herring’s mom, Gloria, said in a text message.

Texting helps a lot when she’s not at school or at a game, but school policy understandably forbids it in class. Two interpreters, including Zirnheld, have taken turns accompanying her to class since she started at LCMS, and Wilson said the arrangement has worked out just fine.

“She’s good about asking questions, she’s not bashful about that at all and she’s an advocate for herself,” Wilson said, noting others gravitate to Herring’s personality. “When we do group work, she’s never the odd man out — everybody wants Bella in their group.”

Even though middle school worked out pretty well, Herring doesn’t fully know what to expect at Lincoln County High School when she starts ninth grade in the fall.

“I’m nervous,” Herring said. “Very nervous.”

She was teased some at LCMS, but it wasn’t anything she couldn’t handle — she just ignored it and focused on her performance.

“I know they look at me as being different, and it doesn’t bother me — not everybody thinks that,” Herring said. “Some people are awkward or unsure of how to communicate with me, so I’m going to have to get all those high-school students used to how they can communicate better with me.”

LCHS does offer a sign-language course, and Wilson said many of Herring’s friends from middle school have signed up for it to communicate better with her.

Beyond high school, Herring wants to become either a veterinarian or a nurse. “I’m absolutely crazy about animals, and I like helping people, so those are two ways to do it,” she said.

To that end, she’s already thinking ahead about college, and she plans to continue playing softball and volleyball throughout her education. She said she might start out at Somerset Community & Technical College, but she ultimately wants to finish her undergraduate degree at Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond.

So what’s Herring’s motivation, and what helps her beat the odds in a school system designed for the hearing-enabled?

“I think a lot of people think that deaf people are incapable of doing things on their own, and, for me, it’s just proving to people that I can do anything I want except hear,” she said. “A lot of people think that deaf people don’t have the intellectual ability or the capability in any form or fashion to do or achieve things in life, and I just hope to prove them wrong.”

To the deaf people who might read her story, she offered some insight and encouragement:

“I want them to know they, like me, can do anything they want to except hear, and encourage them to try to be successful in life,” Herring said. “They’re just as good, if not better, than people who can hear.”