Local ‘Rosie the Riveter’ returns to former Indiana plane factory

Published 1:39 pm Saturday, June 3, 2017

- Photo contributed Connersville Mayor Harold Gordon presents 93-year-old Flossie Smith, of Stanford, with a key to the city on May 12 as a token of gratitude for her time spent working there during the World War II.

Photo contributed

Flossie Smith, 93, revisited a factory where she worked during World War II in Connersville, IND.

CONNERSVILLE – At 93 years old, Flossie Smith returned to the Indiana town she called home during World War II. She went back to the factory where she, like millions of other women across the U.S., went to fill the jobs left open by men who had gone to fight – a collective effort that later earned the women the iconic name ‘Rosie the Riveters.’

It was 1942 when Flossie, fresh out of high school, became a Rosie the Riveter as women quickly replaced men on assembly lines and helped build planes, bombs and other weapons to aid the war efforts.

As the lyrics “that little frail can do more than a man can do” spread across the country, much like the Rosie mentioned in the iconic song, Flossie worked at a factory while her boyfriend, Frank Smith, enlisted and left to serve.

“I stamped serial numbers on little pieces that went to (airplane) wings,” she said, reminiscing about her time at American Central Manufacturing Corporation from her home in Stanford last week. “It was a little machine that you just put a little piece in and stamped a number on.”

There was another women close to Flossie’s age who worked at the factory and the two Rosie the Riveters grew close as the war continued. They remained close long after it was over, until her friend’s passing a few years ago.

But back then, Flossie, a native of Preachersville, was often left to wonder about the fate of Frank, as letters would often take weeks to arrive. The two had been dating for seven months when he left to fight in the war, she said.

Frank served as a U.S. Army medic in the 92nd Medical Gas Treatment Battalion and fought at the Battle of the Bulge, where he suffered frost bite, according to news archives. For three months, he served as a medic in Dachau (Germany) Concentration Camp but for the entire duration of his service, he wrote letters back home to his sweetheart in the states.

“Of course, overseas sometimes it would be weeks that I wouldn’t hear from him,” Flossie said. “You just had a lot of wonders, you know, about what was going on.”

Flossie waited for his letters and continued working in Connersville.

“I started out making one dollar an hour and thought I was getting rich,” she said, laughing. “I think Palm Beach was paying about 46 cents at the time. I was on easy street.”

Easy street wasn’t so easy though, as she walked across the canal bridge to the factory every morning and worked eight-to-ten hours before returning home in the evening.

She was later joined by her cousin Dorothy Duvall, also a native of Preachersville, and the two lived together at Flossie’s aunt’s home.

Flossie didn’t mind the hard work, she said, but the war made some aspects of life less convenient for those who remained stateside.

“Things were rationed. You couldn’t buy shortening, shoes, gasolines, bobby pins. It was hard to get bobby pins,” she said.

When Frank returned in 1945, Flossie was 22 years old and waiting.

“Of course, 22 was plenty old to get married, but my daddy said, when I was fixing to get married, he said, ‘Now you know what you’re fixing to get into is a lifetime thing?’ I never said a word, but I thought, ‘Who would want anything less with that Frank Smith.’”

Frank came home, picked her up and the two were married the following January – and remained so for 56 years, eventually settling back down in Lincoln County.

A key to Connersville

When Flossie’s daughter Patsy Thompson recently suggested she and her mother take a day-trip somewhere, she said Connersville is where Flossie wanted to visit.

“She said ‘I’m afraid it’s changed so much,’” Thompson said.

But Flossie’s return to Connersville 72 years later was met with a surprise visit by Mayor Harold Gordon, who presented her with a key to the city on May 12 along with a letter of gratitude.

“Your service has not gone unnoticed,” the letter reads. “Our community is blessed because of people like you.”

Flossie returned to many places of the past like the factory where she worked, the church she attended and her aunt’s house where she stayed until the war was over.

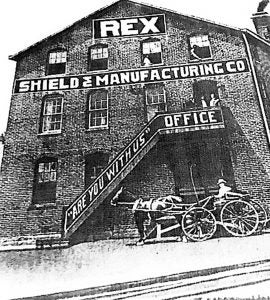

Connersville has certainly changed over the last 72 years. The bridge Flossie walked over every day remains, but no water runs beneath it. The old factory building where she stamped serial numbers on airplane wings still stands, but a new less war-worthy industry now fills its space.

The one thing that remained the same was a small shop where she bought her favorite set of glass bookends, which remain in perfect condition on her desk at home in Stanford.

Photo contributed

Connersville Mayor Harold Gordon presents 93-year-old Flossie Smith, of Stanford, with a key to the city on May 12 as a token of gratitude for her time spent working there during the World War II.