State, local historians aim to document earthen Civil War fort on mayor’s property

Published 10:29 pm Thursday, September 22, 2016

- Photo by Abigail Whitehouse Martha Francis, of the Lincoln County Historical Society, points in the distance as Mayor Eddie Carter and Stuart Sanders of the state historical society look over a historical site.

- Photo by Abigail Whitehouse Gambrel holds up a .69 caliber mini-ball which was found by Glen Campbell who lives just to the left of where a portion of the original Dix River Bridge still sits.

- David Gambrel and Sanders review a historical map near the old Dix River Bridge.

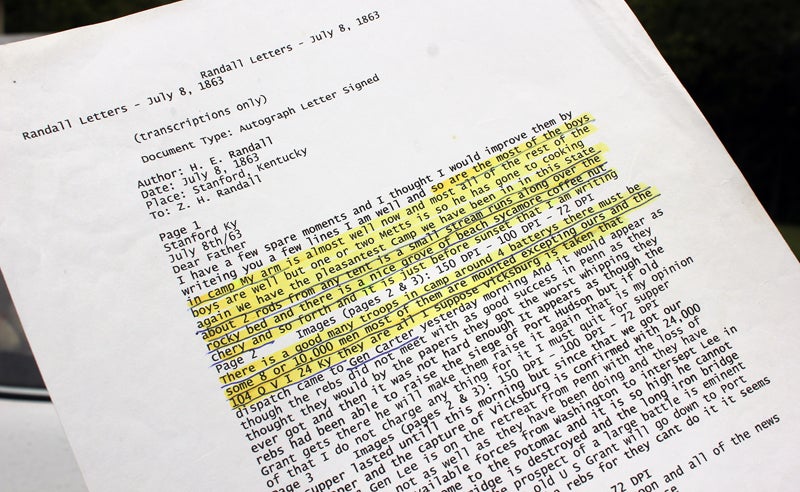

- Photo by Abigail Whitehouse Shown is a letter written by H. E. Randall to his father on July 8, 1863 from a camp in Stanford. Though the name of the camp is never mentioned, Mayor Eddie Carter believes the description points to the fort believed to have been located on his property.

Earlier this month, state and local historians gathered at the site again to assess the scene and brainstorm ideas for tracking down historical documents to back up the claim.

Carter knew the hilltop pasture, situated on U.S. 27 across from the Dix River Golf Course, was historical but it wasn’t until the state road department began discussing expanding the roadway in front of it to four lanes that Carter intervened and experts flocked to the scene.

Another expert, Stuart Sanders of the Kentucky Historical Society, recently visited the mayor’s farm to gather information to take to archivists who he thinks will be able to help find the documents needed to declare it as an official historical site.

“It’s just an ideal spot when you get to thinking about it,” Carter said. “You don’t appreciate it until you get up here, how strategic of a location it is.”

According to research and knowledge of Carter, local historian David Gambrel and Martha Francis of the Lincoln County Historical Society, the site was home to a large number of Union troops in about 1863. The hill provided a safe outlook for Union soldiers and an uphill struggle for Confederates, with a number of cannons strategically placed as well.

“There’s plenty of water here, there are springs, there’s a creek down there,” Carter said. “You could’ve gotten a lot of people here. They could’ve camped down in this bottom here and been pretty safe.”

Gambrel said the gaps between the mounds atop the grassy hill were likely where cannons were placed.

“If they were trying to do something to Dix River bridge, from this distance they could’ve burned it up,” he said.

Protecting the roads after all of the calvary raids would have been another big worry for the Union troops, Sanders said.

Other historians who visited the site before said they believed the fort was built as a line of defense to protect transportation routes in central Kentucky.

“This is pretty amazing,” he said. “Hopefully we can nose around and find out who lived here, who owned it. Then you can get the war claim from the national archives.”

A war claim, Sanders explained, is something that property owners submitted for reimbursement after the Union Army damaged or used their property.

“So after Perryville, for example, a lot of churches and schools and private individuals tried to get money back,” he said.

The goal of the group of historians is unanimous – keep the site from being damaged or destroyed and find documentation to prove that it should be preserved.

“Documentation is what you need,” Francis said.

Additionally, Sanders said there is currently a project underway to digitize all of the governors’ papers from the Civil War, which he said could be another avenue for finding documentation on what Carter believes was called Camp Burnside #2.

“I have a lot of information where Camp Burnside #2 is referred to. It just makes sense,” Carter said.

In one of several letters Carter has found, an H. E. Randall writes his father from Stanford on July 8, 1863, telling him of the camp he was in with several others. Randall claimed there were around four batteries – 8 to 10,000 men – at the camp and that a small stream ran closely alongside his tent.

In another letter Carter found during his research, a man writes home to his parents and says “we’re camped in danville and we’re going in the morning to camp burnside, ten miles to the south.

“We’re (Stanford) approximately 10 miles from Danville,” Carter said.

As the group traveled a bit further down U.S. 27 to the site of the old Dix River Bridge, they discussed the potential of the site once it’s documented and marked with talk of trails and interpretive signs showcasing the history of it all.

As an avid lover of history, the curiosity still looms for Carter as he and the group continue to dig through documents in search of proof.

Carter said it may take a trip to Washington to track down the proper records but once that’s accomplished, he would like to put up a historical marker and secure a historical preservation easement on the property so plans to expand U.S. 27 to four lanes doesn’t interfere with the site.

“I would just love to find the actual name of it and I’m hoping Stuart and David and Martha, all of us together, at some point can get the records,” Carter said.