School district continues talk on nickel tax

Published 6:15 am Thursday, July 6, 2017

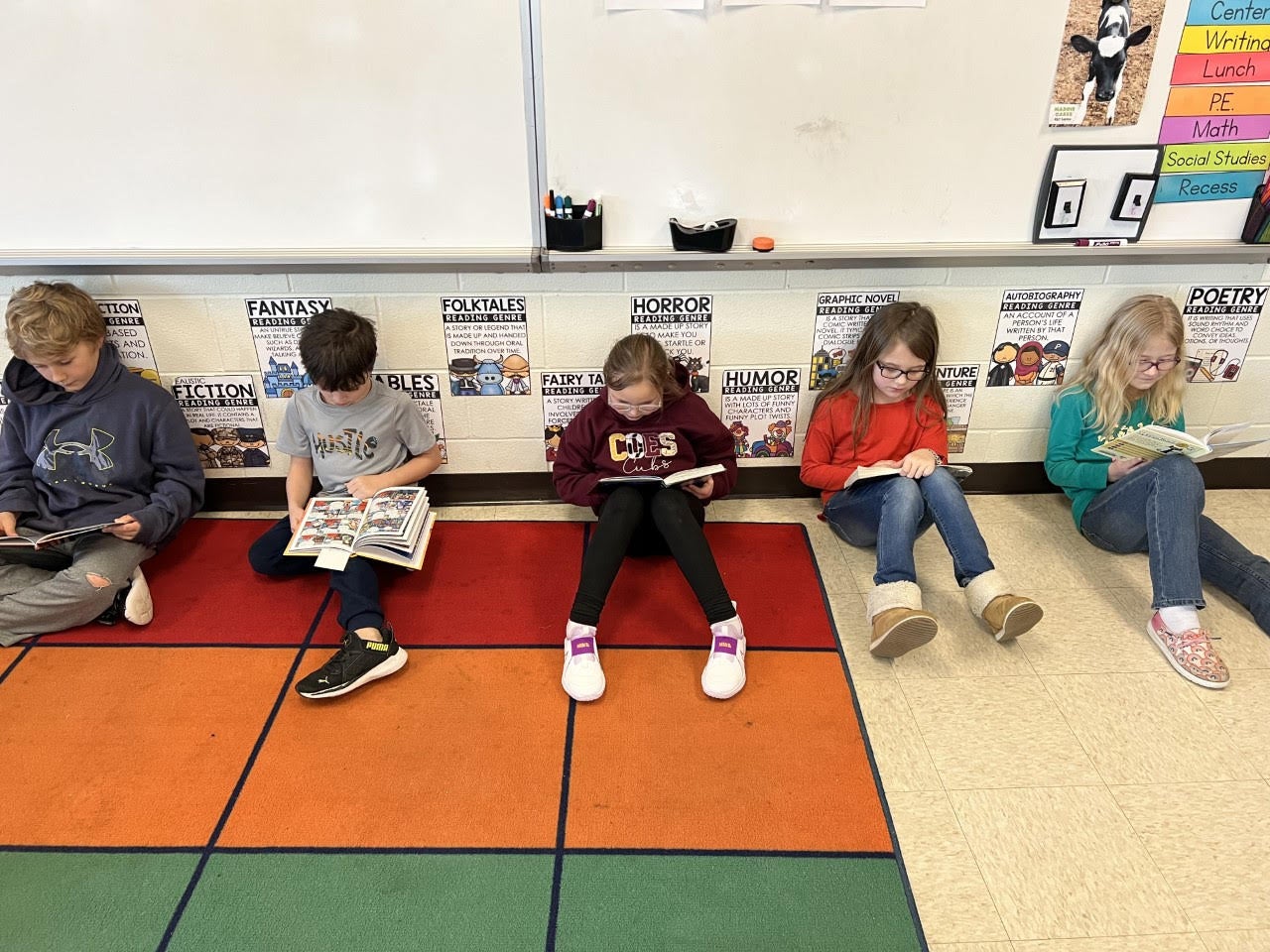

- Photo by Joshua Qualls About 30 people showed up at the special-called Lincoln County Board of Education meeting Thursday for discussion on the recallable nickel tax.

By Joshua Qualls

STANFORD — About 30 people attended the Lincoln County Board of Education’s special-called meeting last Thursday for continued discussion on a recallable nickel tax, which failed June 8 for lack of a second.

Twelve people delivered opinions on the proposed levy and asked questions for clarification on what impact it might have on the county. Superintendent Michael Rowe praised the comments as signs of democracy at work.

The majority were opposed to building two new elementary schools with the money under a consolidation plan, which had been proposed before the vote, while some just opposed the nickel tax itself. Even though the levy would require two separate board votes for it to be implemented, one to approve the nickel tax and another at a later date to decide how to spend it, some of the taxpayers in attendance were wary about approving it without first knowing exactly how the money would be spent.

“The building doesn’t teach our kids anything, I mean it’s the teachers that teach our kids,” said Jason Elliott, echoing common concerns about using the money to fund new construction projects. “Not that I’m against the nickel tax if it’s needed to pay off some debt, but … let’s get it down to where it’s going to go. It needs to be outlined.”

If brought to another vote and approved, the levy, along with an expected state match, would boost the district’s bonding potential from $3.2 to $21.1 million. The revenue generated by the nickel tax is earmarked specifically for new construction, renovations, paying off existing debt or purchasing new property over the next 20 years.

Instead of building new schools, Elliott and others suggested it could be used to pay against the $30 million in bonds that the district already owes. This would mean that the district could essentially use the money to refinance its existing loans.

What’s more, four current schools — McKinney, Highland, Hustonville and Waynesburg — would be shut down under the consolidation plan, creating logistical obstacles for teachers, parents and students across the county. But some of the schools, McKinney for example, are in serious need of repair, a fact not lost on any of the board members.

“There’s no doubt they need work done to them,” said District 4 board member Alan Hubble, who voted against the nickel tax because he was concerned about how the funds would be spent. “It’s stuff that’s been put off for the last 15 or 20 years, and I’m not blaming it on any one person. I don’t know who’s responsible, but it still needs to be taken care of and it’s not stuff that we can just pawn off.”

Lincoln County Middle School teacher Debbie Francis, who supports the nickel tax, agreed with Hubble, noting she has garbage cans in her classroom’s windows to deal with leaks from rain.

“Every time it rains, I have a river,” she said. “There is a definite need to improve the buildings that we have and to have buildings for our students that are up-to-date and modern.”

Other concerns dealt with the nickel tax’s potential short-term impact on farmers and other taxpayers.

County magistrate Joe Stanley, for example, said he couldn’t justify making taxpayers take on the extra burden because they are already paying more than enough.

“If you go back to 2006, we were paying 37 cents out of a dollar to school board taxes. Fast forward 10 years, we’re paying 52 cents,” Stanley said. “It seems to me like the taxpayers have bent over backwards to do all they can to make this work, and I don’t see how we can ask for anymore.”

Boyd Coleman agreed, adding that the nickel tax would have a negative impact and said and that he is “sick and tired of certain groups of people helping pack the load.” He also predicted that the school district’s current buildings would last for years to come.

“I don’t want to take (anything) away from the kids, but a new building’s not going to help the kids any,” Coleman said. “These buildings will all be here when we’re dead and gone — there’s not one building that’s going to fall down in the next 10 years. I think we can patch them, fix them and go on, but if you spend this many million dollars and that building’s only good for 45, 50 years, there’s something very wrong.”